Education’s Elephant in the Room

We devote a lot of resources to trying to equalise student outcomes, but under ideal learning conditions, individual differences in student achievement widen, writes Russell T. Warne.

This essay is a lightly edited transcript of a speech that the author delivered at the Psychology Without Borders conference on 10 March 2025. The speech can be viewed here.

I have always been fascinated by human learning, but the cognitive psychology approach to studying learning did not appeal to me. I was not interested in laboratory studies on learning and memory. I was far more interested in the classroom. That is why I decided to study educational psychology in graduate school. Educational psychology is much more applied than cognitive psychology.

However, most educational psychologists share a common interest with cognitive psychologists in understanding how a change in conditions results in an average change in an outcome. Both groups pay little attention to individual differences. The cognitive psychologist generally sees individual differences as random “noise” or “error” that needs to be cancelled out by averaging scores in a group. Even under the carefully controlled environment of the laboratory, individual differences in learning remain. But that is not random “noise” to ignore, it is an important phenomenon to understand.

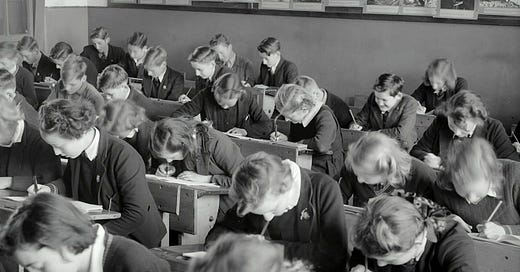

Educational psychologists also see individual differences in their work, but their reaction to them is different. Rather than ignoring them (as the cognitive psychologist does), most see individual differences as a failing of the education system—especially if struggling students don’t meet the standards set for them. In the United States, the dominant educational policy goal is to reduce achievement gaps between rich and poor, between states, and between individuals. We devote a lot of resources to trying to equalise student outcomes. However, when schools have a good curriculum and experienced teachers, individual differences in student achievement widen. Yes, struggling students do perform slightly better—but the most able students show greater gains. This is a classic example of the Matthew effect.

It is not just ideal learning conditions that fail to eradicate individual differences. Equalising learning conditions has the same effect. After the communist revolution, the Soviet education system was reformed to equalise school environments as much as possible throughout the Soviet Union. During the 1920s and early 1930s, educational achievement tests showed that some children were still learning more than others. So, in 1936, the USSR banned standardised testing altogether. It was much easier to ban the tests and hide individual differences than it was to actually eliminate them.

Equalising educational environments often magnifies individual differences in learning. I recently saw this firsthand when I observed the classroom teaching at the United States Army’s Future Soldier Preparatory Course. This is an educational program that is designed to help aspiring recruits pass a test needed to enlist in the army. This three-week course is the most equalised educational environment I have ever seen in my career. All the students wake up at the same time, eat the same meals, dress the same, and attend classes with the same excellent curriculum. They even have the same haircut. All of them are extremely motivated because they want to join the military, and they are paid for their time attending the course. The classrooms are completely free of distractions, such as cell phones. And with a drill sergeant in the room watching the students, there are zero behavioural problems or disruptions. Despite this ideal and equalised classroom environment, individual differences in learning speed and in mastery of the curriculum were not eliminated. If anything, they became more obvious than in a normal classroom. When everyone is treated as similarly as possible, the individual differences that remain become harder to ignore.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Quillette’s Substack to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.