There is nothing that exists so great or marvellous / That over time mankind does not admire it less and less.—Lucretius

What have the Romans ever done for us?—Monty Python

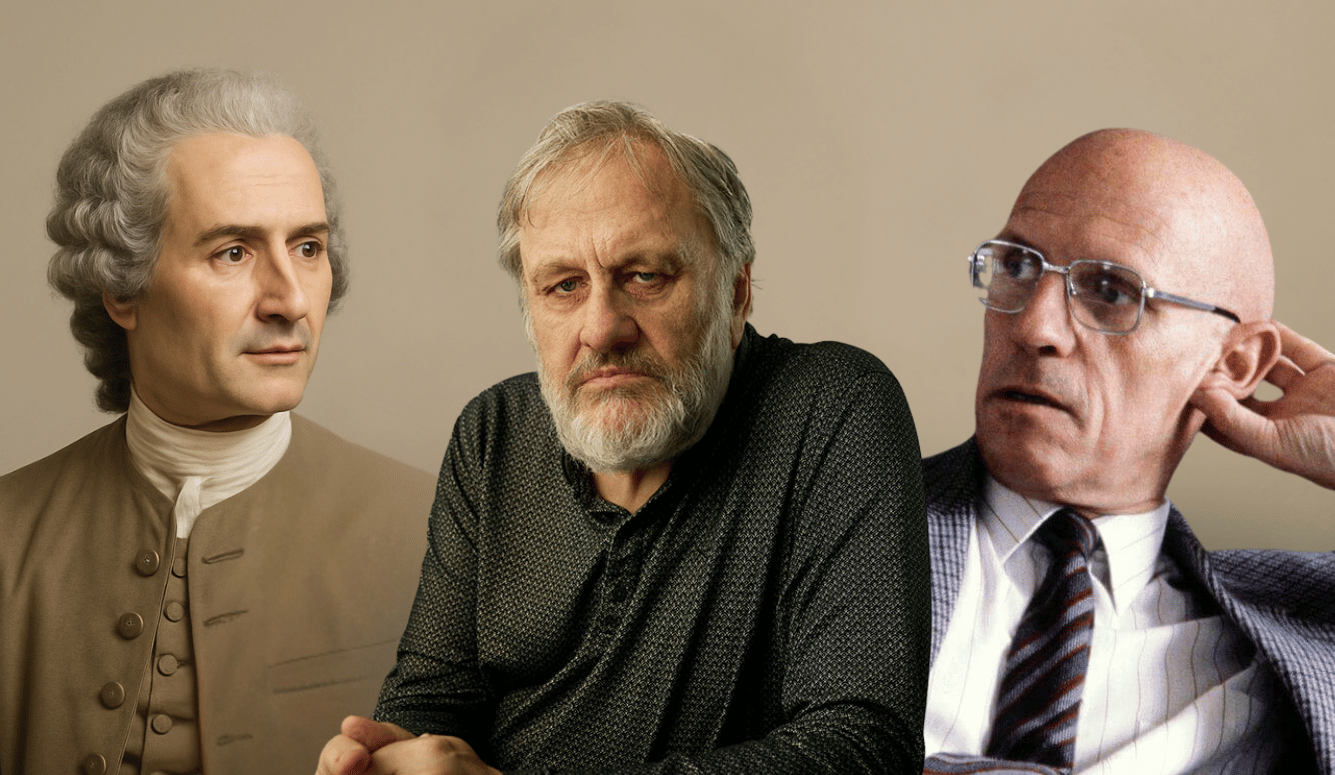

It was as though he had been struck by a bolt of lightning, Jean-Jacques Rousseau would later recall in his autobiographical Confessions. The aspiring young philosophe from Geneva had been casually leafing through a copy of the literary magazine Mercure de France, while taking a brisk walk from Paris to Vincennes, when he stumbled upon an intriguing announcement. The distinguished Académie de Dijon was offering a prize for the best essay to answer the following question: “Has the reestablishment of the sciences and arts contributed to the purification of morals?”

This famous walk took place in 1749, at the height of the Republic of Letters: a vibrant community of intellectuals from across Europe who exchanged correspondence, wrote for periodicals, and mingled in salons to discuss radical new ideas. A few decades earlier, the Mercure de France had played a leading role in the famous Querelle des Anciens et des Modernes, the great debate about whether the modern age had surpassed the achievements of antiquity. By the end of the seventeenth century, the debate had been all but settled in favour of the moderns, thanks to the explosive advances of the sciences. But now the Académie de Dijon was posing a different and equally pressing question: Has all this undeniable scientific progress also led to moral improvement?

If our young philosopher had been astride a horse, he would almost certainly have tumbled off, much like Saint Paul during his conversion on the road to Damascus. Rousseau recounts, “Within an instant of reading this, I saw another universe and became another man.” In a feverish vision, he at once apprehended the innocence of humanity in its original state and the depravity of our civilisation. By the time he arrived at Vincennes, he was teetering on the brink of delirium. His response to the prize question—composed during sleepless nights and dictated from his bed to his secretary each morning—was a sweeping indictment of civilisation. Far from elevating and refining the human spirit, he argued, the advances in sciences and arts had corrupted and degraded it. Rousseau depicted a stark contrast between the blissful ignorance of primitive peoples and the vain sophistication and decadence of so-called “civilised” ones. Wherever the sciences flourished, he argued, virtue withered. Throughout history, civilisations inevitably crumbled under the weight of their own pointless knowledge and arrogant refinements, only to be overpowered by robust, untamed “barbarians.”

Rousseau’s first Discourse is one of the earliest instances of something that would come to accompany modernity wherever it gained a foothold: biting the hand that feeds you because you know it won’t punch you in the face. Just consider what’s going on here: An erudite and cultured philosopher pens a diatribe against the acquisition of knowledge, to be read by the intellectual elite of France and Europe. In eloquent prose that displays his knowledge of both ancient and modern history, Rousseau denounces refinement and scholarly pursuits. And yet Rousseau himself made significant contributions to Diderot and d’Alembert’s famed Encyclopédie, the crown jewel of the eighteenth-century French Enlightenment. As a gifted composer and musicologist, Rousseau wrote the bulk of the articles on music.

Diderot was still a close friend of Rousseau’s at this time, though they would later have a bitter falling-out. He not only proofread Rousseau’s essay but encouraged him to enter it for the competition. Was Diderot swayed by his Genevan friend’s indictment of civilisation? Not at all, but he relished the provocation: here was a leading encyclopedist taking down the whole Encyclopédie project! Diderot’s open-mindedness encapsulates the Enlightenment in a nutshell—a profound appreciation for fearless self-criticism and for the relentless clash of ideas, even to the extent of inviting one’s adversaries to give you a thorough intellectual thrashing.

Rousseau predicted that his essay would be met with a “universal outcry against him,” and that only a handful of enlightened—or perhaps unenlightened—souls would truly grasp the force of his arguments. “But I have taken my stand, and I shall be at no pains to please either intellectuals or men of the world,” he declared. The irony is that the learned Académie awarded him the first prize.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Quillette’s Substack to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.